Entry Point by Krista Pasini

In early 2017, I began to have frequent dreams of a girl in a hospital gown, wandering barefoot in landscapes devoid of others - as though she'd escaped from a hospital to find no one else existed. The dreams began after research I had done on the many ghost towns that remain across the state of Montana, reminders of settlers, gold rushes, and encampments from a century ago. I recognized that a complicated backdrop had a lot to teach me, as did the girl - who I saw as a reflection of my former self, searching to connect with the present. She was looking for a home within herself, and so I decided to follow that wandering girl into the local landscapes. The curiosity of being in the present tense called to me and I considered the way maps state "you are here" as a way to orient myself within the terrain. I questioned whether maps could identify my location in the experiential and fluid ways I sought. I was trying to find the location I had departed from, and in so doing I reconnected with the shadow in my dreams.

History for me wasn’t about memorizing dates or names. Instead I was guided by professors in my undergraduate honors program to first view the text of any historical record as a story and then question the source of that information. We were encouraged to “tilt the lens of the kaleidoscope,” to see a crucial moment in history from a different perspective, so that other voices or perspectives might come to light. I found this practice intriguing and addictive – it aligned with a responsibility that I took from Donna Haraway’s words to stay with the trouble, with the urgency of Anne Bogart’s essays to be vigilant, and also Hilton Al’s recommendation - to follow a story to its source material.

After spending decades in a form of classical training that required a rigid exactitude with unnatural aesthetics, I remembered a time in my life when I wasn’t yoked to a studio with a mirror reflecting my technical errors, or a tempo requiring I move a certain way. Reminded of a girl who grew up near the fields and riverbanks of a small country town on the high plains of Montana, I considered how different my experience of playing in the mud, climbing trees, and catching grasshoppers was in comparison to the structured, formal, and delicate world of dance as I knew it.

Revisiting an earlier inquiry, “how do we embody our environment and how does it embody us?” I investigated Harrison Owen’s Law of Mobility further. Through that lens, paired with my undergraduate training, I re-framed what would become a paradigm in my creative practice: art making as performative research in relation to historical inquiry. I relied upon the experiential process of Deep Listening to Phenomena as a choreographic intention and resolved to be present for what I was experiencing throughout the process – to witness the spaces and myself as part of that landscape – blurring the lines of performativity and authenticity ... site and self.

The more I shined my flashlight into the corners of my interior wandering, the more I became aware that my familiarity with my exterior wandering was limited to the experiences I have encountered. I also reflected on how home is, can be, and often must be, where our feet are planted. For large communities, not just human, a rooted homeland or a safe place are unavailable, destroyed, or taken. In some cases, going somewhere else is not a choice.

I became interested in instances where that choice was available, and the privileges afforded in that mobility. I became acutely aware of how the location of “home” even amid less than ideal environments still nurtured life; and for many species, not just human, there was a commitment to survive. Drawing my inquiry out further, I pondered how we are tethered to the earth and equally tethered to ourselves as hosts with diverse ecosystems living on and within our body. I began to consider myself a home, a place, for the metropolis of microbes relying on my health and wellbeing for their survival. I asked myself how I might be a steward of my own ecosystem and how that form of empathy might translate to empathy beyond myself. As I travelled around Montana, I made an intention to be present to each place, myself included, and to be mindful that the locations I visited were homes to others.

A resonating aspect of this project was how we use, extract, and harvest resources from our environment and the ways in which those behaviors and actions translate into how we use, extract, and harvest from each other, and ourselves. In Montana, the scars of massive resource extraction are juxtaposed with beautiful picturesque landscapes, and even in circumstances where the water is toxic communities remain dedicated to their home. I was interested to understand how familiarity lends to empathy, and how the stories of a place might instill compassion.

This became a site specific performance research project exploring the state of Montana and considering its frequently used moniker of the same name. I used this nickname as an initial question and pondered where there last best place was. Which led to additional questions about “What is place?” or “How do we quantify ‘best’?” I began asking embodied questions, “If your body were the state of Montana where would your heart be?” “Your hand?” “Your voice?” These questions were often conversational, and I learned about Montana through their stories. I learned the Wise River holds someone’s heart, and Billings is someone’s right hand because it feeds them, and the asbestos mine in Libby is someone’s lungs. I quickly discovered my committed presence to listen to their stories was an incredible way to hear about the places they had affection and, in some cases, resentment for. These were often places not mentioned on tourist maps or postcards.

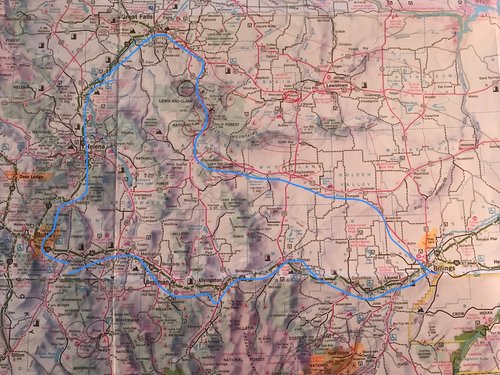

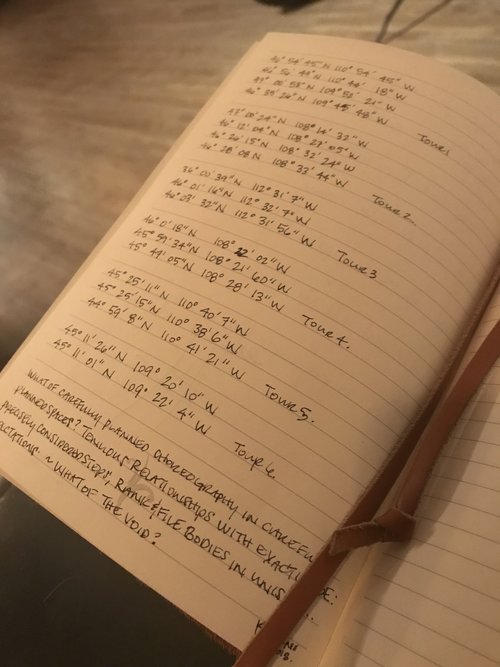

I toured for six months to locations around the state as a contemplative reconnaissance and meditation on performative phenomenology. Each outing was designed as a performance tour and included multiple performance locations resulting in over 84 performances and 28 sites. 19 of those sites are archived. Along the way I documented the coordinates of each performance in a log journal using a compass as confirmation that I was there – in the present tense. This journal became a catalog of longitude and latitude, short descriptions and observations of the place, as well a collection of deep listening reflections.

I took into consideration how my physical self is a location, a permanent residence that carries the scars and secret authors of my story. I reflected on how I tell stories about my body is not unlike how I talk about the history of the landscapes in the region where I live, and that siting specific locations where an injury took place wasn’t that different from how I refer to superfund sites around the state. The way the story is told, retold, and recorded has a significant impact on what is remembered about that place ... or person. I concluded that I gain more insight from “tilting the lens” on the stories I tell, and the stories told on my behalf. I asked the question, “who’s speaks for us in our absence?”

I’ve found that my classical training, while in some cases is functional or aesthetically appropriate, creatively hobbled me. Stepping outside the classical form, and the places it exists, reconnected me to a former part of myself I’d long forgotten: the country girl that played outside in the mud, uninhibited by conformity, and mimicry. In the void, I found how much larger my art practice actually was, and that dance functions as one form of communication, and as an interpreter. My choreographic style supplements when words are too precise or in some cases limiting. I discovered that my relationship to dance was a conduit for empathic connectivity and a method of processing what is not yet ready to be spoken in other forms. Being trained to move in nuanced and intricate ways due to decades of technical practice had translated into an obsessive over-awareness of myself in space. I wanted to challenge that training. The movement I built was influenced by poetic and improvisational prompts. These influences melded together into a phrase of choreography that was structured, but playful. I wanted to “live” with this choreography in a durational way. Each site informed the movement and contributed to the choreography - adding and adapting. Offering additional nuances and details ... memories ... that remind me of the site on that particular day.

Typically, choreography is created for a performative event and then it disappears into the ethers of memory and video archival. I wanted to work in a more durational way. The choreography travelled with me for 6 months as I performed at each location. Each site informed the movement; sometimes slow and graceful - other moments sharp and punched. I allowed the sites to contribute, adding nuances and details based on how the movement adapted and responded to the site’s qualities. I learned to collaborate with the space rather than force a precise reproduction of the choreography, which helped me let go of the obsessive tendencies and perfectionism.

Since the movement was constructed without music, character arc, or the gestural signatures I often create from, I was able to be present to the sequence without being clouded by a performative façade. I was present in the movement, which opened my awareness to my energetic response to the history of the site and how my nervous system was responding. I became more porous and reactive to the elements, the sounds, and presently minded to the exchange taking place between myself and my location. Dancing became a response rather than a performance and I engaged in the space using the choreography as a translator to document the empathic connectivity from one place to the next.

Deep listening has a therapeutic component & promotes health, not only for the practitioner, but also for those with whom a deep listener may come in contact with. I found the experience of being outside among other species, who are always deep listening, comforting. This heightened awareness helped me feel more at ease, with a sense of freedom to be playful & explore. What typically was a constant impulse to find order melted away. I realized the more time I spent outside the more aware I became of the way my dance training had choreographed me. The more I observed the creative organization & patterns of the natural world around me, the more joyful I became to find new kin & teachers. These observations were ubiquitous, & I began to notice that the pattern of leaves falling, the flight migrations of geese, or ice floating down a winter river all had a value I had not recognized before. I no longer viewed the source of choreography as a uniquely human experience. I was humbled by the ways I had extracted resources from my body, as a dancer. I was in a constant cycle of extending myself physically - emotionally, even when I no longer had resources to give. Distanced from the dance community, I befriended places that were barren, scraped clear from mining or logging, because I felt pieces of myself were present there.

I mourned places overrun by tourism, so much so that riverbanks were falling in from foot traffic & the fragile ecology was failing. As I grew empathy for the sites I visited, I honored the scars & wounds of myself as well. At first this was expressed through a sorrow & somber dismay, but grew into a new narrative of practical healing. At the conclusion of the site-specific tours, the choreography sequence became a longer phrase woven with performative talismans from each site. Some movements held very pedestrian mannerisms - others more dancerly. The question arose, how to best bring this meditative/performative work to an others so they could embody this experience. I considered how to translate the choreography into a written script. The testing of this notation sprouted a new layer of performative work & vast root system of interdisciplinary inquiries - changing my creative practice and integrating that playful curiosity I once had growing up playing in the mud next to the Yellowstone River.

Excerpt from Unchoreographed, Methodologies for Improvisational Survival (2019)

Medus-hay | Eastern Montana farm land. Photo by Allison Kazmierski of Font & Figure (2017)

Last best Place, Conversations with montata

A SITE SPECIFIC contemplative Engagement [2017-current]

This project, initiated by performance facilitator and somatic guide Krista Leigh Pasini, began with a series of inquiries centered around Montana's popular nickname, 'The Last Best Place'. Montana is a state frequently celebrated for its vast landscapes and access to recreation and the promotional material and tourism language became counter point to what stories were left out of the narrative. Among all the beautiful vistas, glacial rivers, and ancient river beds there are wounds, scars, that tell a tale of resource extraction and forced removal of indigenous people, of cultural genocide. Last Best Place, Conversations with Montana is an ongoing research which interfaces with eco-cultural politics, and embodiment practices.

Last Best Place, Tour 2. PC Allison Kazmierski (2017)

Initial Questions

Where is the "Last Best Place"?

How do we embody the environment and how does the environment embody us?

How can we be stewards of our place and of ourselves?

Structure

To be open to new concepts

The initial inquiry is preliminary and may change

Observations exists under paradigm of maximum structural variation

Analysis is directed toward discovery - of similarities and dissimilarities

Ethical Considerations

How is the past knowable at all?

What is ‘causality’ in human affairs?

What would evidence about the past look like?

How do a person’s personal, political, economic, social, cultural, ethnic backgrounds, sexual orientation and gender identity, as well as aesthetic preference shape the ‘reality’ of the past that is brought to light?

CRITICAL REFLECTIONS Mobility is a privilege

I refer to myself as a settler, a homesteader, and by doing so in conversation I believe it brings forward the stories in the land where I reside, those that have generational roots and those who were systematically removed and relegated to a confined geographical area, stripped of their culture, and forced to adopt other cultures, languages, foods, and entire ways of life. Genocide. One only need follow the Great Northern Railway’s progress across the continent to know how Montana became a vast territory “open to settlers” and then a state in 1897.

Transit, mobility, movement, are the paradigm in the initial work, and several of the ongoing inquiries. While I focused on movement ontology, phenomenology, and lived inquiry – my interest with the open space technology theory by Harrison Owen, “The Law of Two Feet” also known as the “Law of Mobility,” was an undercurrent and focus of my undergraduate and graduate research: how colonization of this continent and in particular, Montana, demonstrates that European colonizers saw humanity and nature as essentially disconnected. This entrenched belief transcended into not only how settlers saw the land, but an entire people who were vilified as savages, disregarded as illiterate, and marked as part of the ‘wildness’ colonists wished to tame. These stories still live in the soil and throughout the ‘Last Best Place’. Owen’s theory to “go someplace else” holds a potent inspiration for me, I use the principles of his work often in somatic conversations pertaining to self-sovereignty and agency. In the context of this project however, I wanted to look at the theory more critically: The Law of Mobility serves as a resource only to those that have permission to move, colonize, settle, and the poster from the Great Northern Railway demonstrates that fully. To be fair, Owen uses The Law of Mobility in a much different context (a method of organizing large groups) but testing it as a long form, lived inquiry also proved fruitful. It framed the initial inquiries and my interest in why Montana holds up the phrase ‘Last Best Place’ and the obvious discord between those that traverse the state as tourists, and those that are tethered to the forgotten, and not-so-forgotten places not mentioned in post cards or photographed for calendars.

To which I concluded, Mobility is a Privilege.

Vintage poster from the Great Northern Railway.

“We are nature, Nature is not something separate from us. So when we say we have lost our connection to nature, we’ve lost our connection to ourselves””

I consider environmental stewardship a tandem part of this long form reflection and I consider the ‘we’ in the following statement to be the ‘over culture’ of American consumerism. We should consider conversations that re-center ourselves as part of the environment. To separate ourselves as a species above others is another example of colonized behavior soaked in anthropomorphic superiority. Environmental stewardship holds ground in the exterior places many typically find activism in, but I offer an additional consideration: can environmental stewardship also be an interior practice? If we consider the ecology of our physical selves, our bodies, equally important and of value to the ecology around us, empathy lies at that intersection. And empathy increases awareness, heightens consciousness, and connects our stories with others. At the beginning of this project, I proposed that an embodied practice rooted in cultural somatics and conscious engagement offers response-ability.

In a epoch that settles more and more into extraction and consumptive practices, mental illness and physical illness is increasing, poverty and domestic violence continues, and I considered how an Aspen Grove I met near the toxic Berkeley Pit, remained rooted in the earth, unable to leave, share similar hardships of those that do not have mobility, who are unable to use their ‘two feet’ or “go someplace else.” I considered how their continued intentions to survive in an inhospitable environment that doesn’t support them, or their children, is a story we already know. A story of a people, once stewards of the soil colonizers now tread upon. And the reflection sent me further: if one does not have feet, how to find mobility? I found answers in the soil and the rhizomatic root systems that teach me the work is not always visible. Aspen groves are all the same tree in fact, not individuals - connected and in communication underground through vast networks. I consider the Aspen I met as a teacher, sending seeds for future generations to propagate; vessels to carry and preserve the stories, the language, of their origin and their insistence to hope – and not just survive. My job was to get out of the way.

Here, Hammered Oil drum lid with foam core triangles floating in water. Krista Leigh Pasini (2018).

As an outlet, I have a process of developing choreographic objects and somatic responses. This process has further integrated my belief that lived inquiry offers more insight into reflections of location and lineage (be it artistic and/or ancestral). It instills a perpetual cycle of curiosity. I found an overlapping ecological connection of self and site and pursued further inquiry into how being present is a cornerstone to my personal practice and my artistic process. The practice of presence destabilizes power structures that often limit accessibility and representation of other narratives. As this work continued additional inquires developed, new conversations, and I offered up the challenge to use my mobility to listen to the many teachers this environment (human and all) had to teach me.

“Humans are part of the landscape, contributing to biological exchange. Within the narrow span of time that Europeans and immigrants from all over the earth have settled on [the] continent, each bioregion and the continent as a whole have been altered. Humans now inhabit the terrain on a large scale [...]. It is time to understand ourselves as co-inhabitants with the land and learn to tell the bioregional stories of the places we call home." Andrea Olsen, Body and Earth

I understand myself more as a Montanan than I do an American, at least at this moment, because it's really all I know. The state, particularly the southeastern corner, has held nearly all my stories. I'm the collected stories of bygone settlers from the forests of Norway, the Viking Scots, and the eastern edge of Holland which have all layered underneath the stories in between their existence and my own. All layered over and through centuries informing me how I (we) arrived here, on this soil.

The more we act in concord with the narrative that we are trying to tell, the more the story [...] becomes a reality. Speak the narrative that you want to realize and then find the appropriate actions to make that story a reality.” Anne Bogart

But what is 'arriving' exactly? The moment my ancestors stepped off a boat perhaps, but it dismisses their story before crossing the Atlantic. Those stories informed and shaped them just as much as their homesteading story. It all brings up thoughts of a chapter ending and another beginning, a demarcation. And when I consider how author Robert Karolevitz described my ancestor's view of the land I understand the deeper weaving of stories beginning and ending: "Buffalo bones were everywhere, giving the impression that an old civilization had died and a new one was about to be born" (Karolevitz, "E.G." Inventor by Necessity, North Plains Press, 1968). The more I consider the tenuousness nature of the word 'arrival' the more I understand the complexities in how stories are held, inherited, and then built upon ... and also destroyed, dismantled, halted.

_ Krista Leigh Pasini, 2018

“Be careful how you interpret the world; it’s like that”

Mapping Presence

Mapping Presence, You Are Here.

Thee project locations were documented and archived through methods of photography, eco-sound journals, and written reflections. Prior to traveling we collected information about the region: tourism material, cultural history, geological data. This information served as a frame for conversations while we drove along highways and dirt roads. Each outing was designed as a performance tour initially and included multiple locations resulting in over 84 performances and 28 sites. Some are listed below.

A note on the word “performance”

Ultimately the long form meditative process along with the historical and ecological research lent to highly emotional and powerful deep listening experiences. The word “performance” no longer aligned, and the movement adapted, responded, to the space instead. These contemplative engagements became a personal inquiry into being fully present to both myself and the space I occupied and sitting with the trouble, as well as the immense joy, that came from those experiences.

Travel journal of recorded locations and reflections

Sample Sites | Tour 1, August 2017

46° 54’ 47” N 110° 41’ 37” W

46° 56’ 49” N 110° 44’ 18” W

47° 00’ 53” N 109° 52’ 21” W

46° 35’ 26” N 109° 45’ 48” W”

Sample Sites | Tour 2, September 2017

47° 08' 00" N 108° 59' 29' W

46° 26’ 15” N 108° 32’ 24” W

46° 12’ 04” N 108° 27’ 05” W

Sample Sites | Tour 3, October 2017

46° 00’ 39” N 112° 31’ 7” W

46° 01’ 16” N 112° 32’ 7” W

46° 3’ 32” N 112° 31’ 56” W

Sample Sites | Tour 4, November 2017

46° 0’ 18” N 108° 22’ 2” W

45° 59’ 34” N 108° 21’ 60” W

45° 47’ 5” N 108° 28’ 13” W

Sample Sites | Tour 5, January 2018

45° 25’ 11” N 110° 40’ 7” W

45° 25’ 15” N 110° 38’ 6” W

44° 59’ 8” N 110° 41’ 21” W

Sample Sites | Tour 6, January 2018

45° 11’ 26” N 109° 20’ 10” W

45° 11’ 01” N 109° 22’ 4” W

Sample Sites | Tour 7, November 2018

Documentation of Travel

This project was conducted by a trio beginning in 2017, and we found moments amid the work to be playful, curious, and grateful. Montana is an incredibly large state and we found the travel, the mobility, just as important to document and reflect on. At times, we intersected with others, or met friends (not always human) along the way. Our interactions were spontaneous, and we often followed invitations from someone sharing a place they loved or held close to their heart.

HIGHWAYS, INTERSTATES, AND BACKROADS

Montana is the fourth largest state in the United States and encompasses almost 150,000 square miles, the same size as Germany, but unlike Germany, Montana has less than 1 million people. The state's communities span between vast highway systems and mountain ranges, making a vehicle a necessary part of traversing the state. The highways are veins and arteries winding through mountain passes, over waterways, and through long and open plains. Lending to thoughts about how individuals refer to these expansive spaces with phrases like: 'No man's land', 'Middle of nowhere', 'Tim-buk-tu', 'The Boonies', 'As far as the eye can see', 'God's country', and so on. As I began traveling in Montana more, I made a practice to research the indigenous history of the spaces I would be interacting with. This research acquainted me with communal hunting grounds, historic moments rarely shared in classrooms, and a bigger understanding of how so much of the Last Best Place is parceled out to private land and recreation with very little awareness to the indigenous history. I also became more aware of the continuous open land defined by unending fence lines: barb wire, jack-leg, smooth wire, and electric. So much of the state is defined this way and I found myself observing the way fences live in our constant view. There's a certain sense of energy in larger cities, bustling through traffic and more densely populated urban communities and, often, communities just blend into one another and there's no separation between where one city ended another began. Montana communities are still very separate from each other, often miles and hours from each other. Despite having such a small population, we live very separately, and in that distance I think many, white settlers, have forgotten the beginning of this region’s story.

embodied documentation

Last Best Place, COnversations with Montana is a project in several chapters, sketches, vignettes, and an unending root system all formed from the initial site specific somatic engagements around the state. Documented through various methods, it also inspired a series of interactive and immersive installation exhibits tested in studios in the spring and winter of 2018. With each site, documentation of the space manifested in sound collections, photography, timelapse videography, contemplative movement responses - as well as collected geological & historical information. The 'findings' of each outing are archived and cataloged and serve as a library to create from.

Some of the items cataloged were derived from an observation, a phrase, or a story that hung along with us as we explored the area. In some cases, descriptions of an area were of interest - especially areas that had been over populated or over used from tourism. A forest camp-site host shared, “it’s a little worn, it’s been loved to death”, a park ranger describing the delicate ecosystem of a frequented tourist destination by saying, “stay on the designated trail, the river is still intact.” We cataloged anything that caught our attention and added it to a journal that is populated with a variety of words, phrases, reflections, recommendations on ‘best places’, unique sightings, and historical and geological information that we found relevant to consider while engaging in our work.

This work is rhizomatic and ongoing, meaning the art work arises in different configurations and connects with other projects. The inquiries are open and allowed to change and the documentation and archives can be reorganized and curated in multiple mediums and often interdisciplinary constructs.

SITE SPECIFIC PROCESS AND COLLECTION OF DATA

1. Choose a direction

2. Introduce yourself

3. Record Presence

4. Listen and respond

5. Collect the sounds

6. Observe the landscape

7. Record a reflection

8. Document pathways

9. Inhale and exhale

10. Offer gratitude

A note on integration and collaboration

I chose to travel with two individuals I felt comfortable doing this work with. My partner Mike Pasini, who served as support to the personal work I was attending to, and photographer Allison Kazmierski who guided my curiosity and stoked my creativity. Both know my research process and were supportive of this experimental creative practice. Exploring site specific work as a solo artist created an immense vulnerability. Embodying documentation meant that I held onto the emotions and energy with each site we visited and my own narrative cropped up alongside the work. As an external practice of documentation, we would document the site’s coordinates (latitude and longitude). This was a process of acknowledging my physical presence as a form of affirmation. As a survivor of my own trauma, the documentation gave a sense of grounding in the present moment. Our decision to stop and engage with a place was based entirely on a felt sense, supported by the research done beforehand and also being mindful of public and private access. Our creative process had a scientific rhythm, methodical and repetitive; and also, a heightened awareness steeped in a meditative practice. As I healed myself, this embodiment practice pulled me into a stronger space to reflect deeply on ecological and genocidal trauma. I began to look outward while simultaneously looking inward. This intentional patterning and practice had a vibration, a frequency, that eventually became part of me - not just when I was working on the project. This process, this embodied way of being, this slower way of engaging with a space or a person has integrated into my every day.

Field Notes

Portraiture by Allison Kazmierski, Font & Figure

““Perhaps I should say that documenting is when you add thing plus light, light minus thing, photograph after photograph; or when you add sound, plus silence, minus sound, minus silence. What you have, in the end, are all the moments that didn’t form part of the actual experience. A sequence of interruptions, holes, missing parts, cut out from the moment in which the experience took place … the strange thing is; if, in the future one day, you add all those documents together again, what you have, all over again, is the experience. Or at least a version of the experience that replaces the lived experience, even if what you originally documented were the moments cut out from it” ”

A QUICK FAQ

“Did you video your performances when you traveled around Montana?” I personally chose to have the work documented in portraiture only because I wanted to release the construct of audience and invest in the stillness of a moment, the partial preservation of a moment - yet so enigmatically qualitative too. Something photographer and collaborator Allison Kazmierski does well.

“Why are you wearing a medical gown?” In all the photo documentation I am wearing a blue chiffon gown created by Tiffany Miller Designs. It purposefully has a medical gown silhouette to it. Part of my own work in this project has overlaps with memory, trauma, and healing. The statement “you are here” resonated with me as a location of survivorship and recognition of witnessing myself in these spaces - which in turn called me to reflect upon who is not in those spaces.

Sound Scape Samples

The sound of a place carries a wealth of information; each site has a unique score that influences the way we respond and contributes to the energy of the space. While many of the these sound files are a mixture of white noise, conversations, and static, each has a distinct memory attached and a 'tempo.’

Raw sound files collected during this project are archived in a library that is used for eco-acoustic projects and audio sequencing.

Some are available below.

Deep Listening Reflections

A collection of poetic responses by Krista Leigh Pasini (2017 - 2018)

DIRT DUMPLING

Tour 1. Photography by Allison Kazmierski.

Young years on the dry and dusty high plains of glacial plateaus. Silty granular textures coating the skin like powder. Sandstone, limestone, fossil baring river beds, jasper and quartz.

Memories of peanut shells and rusty metal treasures, a shoebox of rocks.

The river banks of the Yellowstone were my playground. With my fingernails encrusted with mud I climbed trees and fell out of them too. My shins were purple and blue my knees scabbed over from bicycle wrecks on gravel roads.

I ran through fields of grasshoppers and played with spiders and snakes. I built forts out of discarded lumber and spent hours laying in the grass watching the clouds.

In the hot summers I would cover myself in mud and bake in the high noon sun before running and jumping into the water to rinse it all off just to do it all over again.

My feet, rarely in shoes, shuffled through prickly patches and sharp rocks without a wince. My skin shown copper as the summer sun kept my company. No amount of refinement, good posture, and etiquette training will hide these earth-bound roots.

The tutus, French twists, and polished nails are how I play the part. It’s only a matter of time before they see my raw, muddy, and un-hemmed edges.

I will always be a dirt dumpling

Last Best Place Tour 2, PC Allison Kazmierski (2017)

Loved to death

And from scorched and blackened forests we’ are gifted. Morels and huckleberries, raspberries and young resinous evergreens blanketing hillsides of charcoal and ash.

Sprung forth from the depths of the ocean, upright and on foot, we flourish at the foothills of generosity, lush ecosystems, and insatiable thirst.

Digging further and pressing the balance we ask for more, we ask for it all knowing the ‘Law of Diminishing Returns’ heralds a widened ledge, a point of irreparable repair.

With wild tempests and hell born heat she threatens, she chases us to higher ground. She admonishes us in the only way a mother can, “parched of any resources left to give, I will still find a way to offer all that I have, even if it kills me.”

Last Best Place, Tour 2, PC Allison Kazmierski (2018)

WHAT OF

What of carefully planned choreography in carefully planned spaces?

Tenuous relationships with exactitude: precisely considered steps, rank and file bodies in unison, controlled pathways and spaces.

… expectations.

What of the void?

Immediatism as movement. Unplanned, unknown, generous explorations.

Soundscapes and Landscapes. Intention and Experimentation.

All collaborators of the given moment. An ephemeral canvas, a living sculpture.

What of improvisation as conversation?

In conversation we listen, we answer, we consider, we empathize.

We become an ensemble of immediate dialog. We become our thoughts.

GO FURTHER

Last Best Place Tour 4. PC Allison Kazmierski (2017)

If I fill the tank I can go further, they said.

“Go further” they encouraged, “but not too far, we still need you.”

I believed them.

Open road, refilling again and again to go further still. I promised to return.

I wanted to return. To share what I had found. I thought they’d be proud, I thought I’d be welcomed home.

But I went too far.

“You can’t leave us” became subtext for more apparent intentions.

I was needed, I was useful, but only as spare parts to make a whole.

What once was generosity now feels like scavenging.

INTACT

Last Best Place, Tour 5. PC Allison Kazmierski (2018)

From the center of the earth, pressed upward by molten heat and vented into sapphire waters.

A riverbed decorated with jagged rhyolite and smooth cobalt limestone direct the scalding swirls and mixes with melting mountain glaciers before travelling downstream.

Carefully dipped toes and bellies.

Clouds of steam sequestering a river of humans tucked into the rocky river banks their noise held down by damp humid air.

Beyond this treasured cove a hoarfrost landscape dormant and sleeping, small grey birds diving in search of fish eggs, two ducks paddling against the current.

For those that travel to this thermal source, on foot and through snow, our footprints tear pathways into once lush and fertile earth. Decades of footsteps along a once narrow trail now widened for the thousands of admirers seeking the warmth of the magma core.

Jackleg fences fending erosion, signs requesting feet stay only on pathways. The banks tender from so much attention begin to soften and crumble.

How long before the banks fall in and the shoreline worn bare? When will I be undone, overcome, and tread upon? A recycling of seasons allowing fertile growth each spring.

Another chance to remain intact.

WHO SPEAKS FOR US?

Last Best Place, Tour 5. PC Allison Kazmierski (2018)

Who speaks for us in our absence?

A sharp crack in the ice under a blanket of snow serves as a gentle reminder that much is rushing beneath us. Tread carefully along the shore.

These are your stories, they do not belong to me. Stories carried from the mountains and into the quiet windblown valleys. A lineage swirling behind you. We meet at the shoreline briefly. This is how I know you.

My feet chilled in the snow banks as you’re nudged along by the others.

You join the trees torn loose from the banks of an untamed river you call home. I imagine your story is infinite. I imagine theirs is too.

And when your story is told on the lips of someone else, how do we listen? Knowing that pieces are missing, projections of self intertwined, and interpretation ubiquitous in how each of us sees the world.

Secret Authors

Last Best Place, Tour 7. PC Allison Kazmierski (2018)

Words packed and wound tightly

Infinite histories, endless associations, individual context prismatic

Entangled

How have we shaped and been shaped by the words we choose?

Our collected sentences, the embedded and swift thinking of our observations? Our language?

Tethered relationships,

Generational stories

Handed down memories

Ancestral

Cellular

Present and past

All the secret authors to the stories we tell.

HOw do we extract from each other?

““Butte is one the places America came from. Indeed, it can be looked upon as a national laboratory in which the inner workings of a crucial kind of economic activity are laid bare and United States environmental policy is being put to one of its most severe tests. Butte is where we must return, in the manner of a pilgrimage, if we wish to grasp in full the implications of our appetite […] an appetite that remains unabated […] beyond the reach of conscience.”

EDWIN DOBBS

(“Pennies from Hell,” Montana Legacy: Essays on History, People, and Place. p. 315).

”

Google Earth image of the Berkeley Pit next to Butte, Montana (2019).

The Berkeley Pit is the source of a superfund complex that spans into multiple river systems and soil throughout the region. If you look at the site from a Google map, the names of the minority communities overtaken by the mine expansion are still listed. One of those communities was Meaderville, an Italian community where my father-in-law grew up. His family, and the entire population, were forced to relocate so the mine could be expanded. The Anaconda Mining Company gave little time for families to make arrangements, and the story of St Helena’s church, moved hours before demolition was scheduled, is just one of many examples of how little the large corporation cared for the community’s culture and history. And while some structures were moved, many were simply buried, like the Holy Savior Church. If you visit the Berkeley Pit, there’s a viewing area with recorded information about the pit and the communities it swallowed. Told very differently, the bubbly voice breezes over the event as though it was a mutually benefitting arrangement:

“Hello and welcome to the Berkeley Pit viewing stand […] the richest veins of ore sit where the Berkeley Pit now sits […] plans to enlarge the pit along Butte’s east side surfaced in 1952 […] that decision would affect several historic neighborhoods including Meaderville, McQueen, and Dublin Gulch. They were all swallowed up by mining expansion. […] And while painful, most folks realized that Butte’s economic stability relied on mining. It was a simple fact, if the pit did not produce, it would cost every miner’s family their livelihood.”

“Berkeley Pit Viewing Stand, Audio Transcription, Butte MT.: Pasini, 2017”

“Until we can grieve for our planet, we cannot love it – grieving is a sign of spiritual health. But it is not enough to weep for our lost landscapes; we have to put our hands in the earth to make ourselves whole again. Even a wounded world is feeding us. Even a wounded world holds us, giving us moments of wonder and joy. I choose joy over despair.”

Robin Wall Kimmerer quoting Joanna Macy”

The pit is now an acidic lake. The water is so toxic it has killed entire flocks of migrating geese, not once but twice. The most recent occurrence was in 2016 when 3000 geese died after the water destroyed their throats, stomachs, and melted their wings.

I began to focus on the increasing extractive practices in the region of Montana, and the dysfunctional way the state is nicknamed “The Last Best Place.” I noted the erasure of stories across Montana, places like the Berkeley Pit, that are scrubbed or buried under the toxic lake. I wanted to translate the porous feeling I had when I was there standing over the largest superfund site in the country.

After visiting the Berkeley Pit viewing stand, I drove back to the tailing pond area, hidden by a thick grove of Aspen trees. We hiked through the trees and were able to view the pond and the mining activity, but upon leaving, the Aspen Grove caught my attention. It was a surreal experience, and I left reflecting on my mobility to leave that toxic environment while the trees remained rooted in the soil.

Last Best Place, Tour 3. PC Allison Kazmierski (2018)

AMong the Aspens

Among the aspens my movements halted, branches tucked under my arms, snagging my dress, and curling into my hair. With every moment I began to move my feet sunk deeper into the dark nearly black spongy earth.

These aspens, permanent residents had settled in for winter, their leaves lay at their trunks and decomposing beneath my feet. I was not the performance that day, they were. I was wildly aware that my presence in that aspen grove was welcomed on the condition that I listened, and that I moved carefully among the branches when I left.

To move carefully, so as not to disturb the aspens required awareness of all my limbs, and the spatial exactitude of my pathway between each tree. My movement slow and planned, but not always successful. A branch sliding along my back with momentum would snap back into place often pelting my skin as I winced with apology.

The aspens choreographed the movement, informing my serpentine weaving through their negative spaces. They were my teachers, I their pupil.

Catching the Experience

Choreographic object featuring movement artist Morgan Dake (2018)

“I focus on catching experience in the act of making the world available, offering a counter modality from abstraction and logic to provide ways through which that which is in flux and otherwise unseen can be touched and experienced” (VIda L. Midgelow quoting Van Manen, 75).

Chasing Light Among the Aspens

Multi media somatic performance installation with dance artist Daniel Mont-Eton and featuring artwork from Michael Pasini, Nick Olson, Tiffany Miller O’Brien. Facilitated by Krista Leigh Pasini (2019)

A QUICK FAQ

The white linen skirt, while beautiful to stand in, restricts movement by swirling around the feet - seizing the legs into stillness. The profoundly emotional process of witnessing Daniel Mont-Eton journey through the space, seeking mobility, and falling to the ground became a potent communication towards the idea that mobility is a privilege.

Reflections, Shattered by Michael Pasini mixed media (2019)

Conscious Response, embodied movement

Also known as: How a dancer deconstructs their Eurocentric training

I’ve found that my classical training, while in some cases is functional or aesthetically appropriate, creatively hobbled me. Stepping outside the classical form, and the places it exists, reconnected me to a former part of myself I’d long forgotten: the country girl that played outside in the mud, uninhibited by conformity, and mimicry. In the void, outside of the formal dance environments, I found how much larger my art practice actually was, and that dance functions as one form of my communication, and as an interpreter. My movement style supplements when words are too precise or in some cases limiting. I discovered that my relationship to dance was a conduit for empathic connectivity and a method of processing what is not yet ready to be spoken in other forms. In the process of leaving my training behind, and engaging with other movement methods and theories, I began to align with a more integrated way of being. This allowed me to look at dance, my profession, my self as a white settler residing on the unceded and ancestral territory of the Crow Apsáalooke and the Northern Cheyenne Só'taeo'o Tsétsêhéstâhese people much more qualitatively.

In early 2017, I began to have frequent dreams of a girl in a hospital gown, wandering barefoot in landscapes devoid of others – as though she had escaped from a hospital only to be alone. The dreams began after research I had done on the many colonial ghost towns that remain across the state of Montana, reminders of settlers, gold rushes, and encampments from a century ago. I recognized that a complicated backdrop had a lot to teach me, as did the girl – who I saw as a reflection of my former self, searching to connect with the present. She was looking for a home within herself, and so I decided to follow that wandering girl into the landscapes of Montana. The curiosity of being in the present tense called to me and I considered the way maps state “you are here” as a way to orient myself within the terrain. I questioned whether other forms of mapping could identify my location in the experiential and fluid ways I sought. I was trying to find the location I had departed from, and in so doing I reconnected with the shadow in my dreams.

A QUICK NOTE

History for me is not about memorizing dates or names. Instead I first view the text of any historical record as a story and then consider the source of that information. I frequently “tilt the lens of the kaleidoscope,” to see a crucial moment in history from a different perspective, so that other voices or perspectives might come to light. I find this practice intriguing and compulsory – it aligns with a response-ability to follow a story to its source material.

CHOREOGRAPHIC NOTATION & TRANSMISSION

In July I began working with a phrase of movement that carried different tones and tempos and repeated the pattern daily until it became second nature to execute – memorized, but not so much as in the precise shapes as in the energy and the intention behind the movement quality. I purposely made the phrase outside of my technical training using movement patterning that felt more authentic to myself and my lived experiences. This phrase was a baseline of movement that I worked from during each outing. I engaged with this sequence over 80 times at site-specific locations through summer, fall, and winter. I allowed the movement to be fluid and adaptable to the way a space might influence the patterns and I also began to add movement gestures from each location into the phrase so that the phrase eventually held a physical memory of each site I visited. This long form practice in spaces outside the traditional studio and stage performance environment brought about a rich physical journaling practice and contemplative reflections on the practice of presence and long-term healing.

Curious as to how language can inform, change, and lend to how we interpret story and experiences, I created a detailed notation script based on the movement sequence to explore how others would embody the prompts. I wondered if I could re-create the 80 experiences into a fluid singular re-telling using performative language - something entirely outside dance pedagogy and structure. The script also became a potent reflection on how to best communicate an experience while also considering the expansive ethical requirements needed to create a supportive space for such an interior/contemplative response. With each transmission of the script, the intention was to create a performative exploration rather than a passive visual experience of witnessing me perform the sequence. And by witnessing their responses, it created a healing feedback loop. This practice has continued and each person responds and interprets the prompts differently, creating a unique and authentic choreography of their own.

FIELD TESTING

A QUICK FAQ “What is Field Testing?” This is a frequent question. I began Field Testing as a qualitative/heuristic research and choreographic notation. Field Testing is essentially a form of performative research that honors the ephemeral nature of performance, of documentation, witnessing , authentic movement, and the translation/transpersonal echoes of notation methods. I wanted to observe how an audio script communicates a long form experience and whether those experiences would resonate as an embodied experience. The other half of Field Testing is derived from discussions during a studio workshop series hosted during the same time period as the Last Best Place tours. During those workshops, I collected a series of questions and layered them into the movement sequence. These questions were large, deeply reflective questions to ponder, “how do we protect what we love?” Or “How do we extract from each other?” the weight of these questions is a potent link to the eco-poetics pieces that grew from this process.

“NOTATION SCRIPT SAMPLE

Thank you for engaging in this transmission. Feel free to take a moment and find a space you feel comfortable in. Establish yourself within the space. What is your relationship to stillness? Inhale the air around you and close your eyes. What did your eyes see before they closed? Observe the energy in the space. What does the space tell you? Choose a front. Slowly open your eyes. Look without identifying, instead observe. Lengthen your gaze at something far beyond your natural sight. Imagine what exists out beyond the horizon, what exists underneath you, and in the air above you. What exists within you? Begin to explore the space contemplating, answering, or dismissing the questions through your own movement. Large or small. Seated or standing. Maybe even lying down. Begin to stretch towards a new direction, a new front, twisting the body as you transition, until you’re facing a new direction in the space. What is your relationship to movement? Your energy begins to float skyward, a suspended state, that settles earth bound and you fix your gaze intently forward. What are your resources? Look through a telescope. Sharpening your focus outward. How are your resources extracted? Take a deep inhale. Collect something fragile and look upon it with your heart. What does sympathy look like? Expand your energy outward like an explosion, carrying you into many directions. What is worth? Allow your energy to settle, fingertips drift like smoke carried in the wind, you begin to arc and lean in a suspended position, like a tree in continuous wind. What does balance look like? An energy calls you to another direction as you also attempt to remain where you are. How do you make space for yourself?”

Mapping Presence

Interested to check out Field Testing on your own?

Grab some headphones/ear buds and, if possible, head outside.

Questions about the work, or maybe something comes up that you need to chat?

Message me. I am here.

Additional Field Testing Sound scapes

BIG SKY Ekphrastic Response

Montana tourism frequently markets the sky, as though no one else has one. I wonder occasionally if that is because we are avoiding looking down - at the trauma turned into the soil. I will admit, there is something about the expansive Montana sky line, it catches individuals from other places of the world often in a transcendent pause. After decades of living in Montana, I still fall in love with it too. There is a lot of sky to look at and plenty of places to perch allowing the eyes to stretch out on the horizon. This ongoing documentation and collection of 'sky-scapes' is a media journaling project that considers if one is rooted in the soil, the sky perhaps offers us dreams of flight, of mobility.

In an ekphrastic response, I collected and curated a series of parabolic weather camera footage and layered it with a sound artist and voice overlay to mark the experiences of what felt more authentic and complicated - a visual experience that reflected my interior ecosystem. Similar to Field Testing, I was interested to see how someone else might respond. I offered the documentation as source material to visual artist Nick Olson who responded with a kaleidoscopic video loop, Title in Time, to the project’s conversations about Montana’s other often used nickname, “Big Sky Country.”

Wish You Here

Photography by Allison Kazmierski

Words by Krista Leigh Pasini (2019)

Lift up indigenous art and indigenous culture

Supaman, Christian Parrish Takes the Gun, is a light I continue to share and find inspiration in. When I think about dance in Montana, I think of him - his willingness to share his story so generously and how his artwork and collaborations bring brightness to the world. In so doing, his joy is resistance.

“We went to all the pow wows when we were young. At that time children could not dance. Only people over 50 years of age could dance. Most people do not know this, the government forbid children to dance Indian and that’s so they could wipe out the culture of the young people, and finally the new generation would never know what happened.”

Apsáalooke Nation Elder (Transcribed via Nakoa Heavy Runner and Christian Parrish Takes the Gun, Warriors Prayer).