“This thread looks closely at Eurocentric dance history in Montana, which is a lineage I belong to and have relation with. That is not to dismiss the deeply rich, spiritual, and historic dance traditions of the indigenous nations that reside within the Montana state borders who have and continue to care for, and share, their dance art and spiritual lineages. A tradition, I might add, that was at one time forbidden for individuals under the age of 50. If you are not familiar, I highly recommend finding opportunities to learn more and show up for events where indigenous dancing is shared publicly.

Inspired by: Nakoa Heavy Runner | Warriors Prayer with Apsalooke Dance, Music Artist and Activist Supaman. Resource link provided at the end of the document.”

As each of the three women, all with shoulder length silver hair, gathered in a sunlit room for a photoshoot, there was a discussion about the attire. “How about all black?” Bess Snyder Fredlund offered as a color suggestion, to which Betty Loos agreed. Bess Pilcher Lovec shared a teasing threat of showing up in a bathrobe because the instructions said, “comfortable.” The photographer, a former student of Loos, directed all three into standing and seated poses as I prepared a microphone and notepad for our meeting.

I had heard stories and brief references to Montana dance companies that have come and gone over the decades. These references would be simple conversational anecdotes over dinner, “I was part of a professional modern dance company in the 70s.” Another story included information about performing a piece set by renowned choreographer Bill Evans, or hosting national dance artists like Joe Goode for workshops at Eastern Montana College (now Montana State University – Billings). Over the years, I pieced together a rough sense of timeline and reoccurring individuals. What caught my attention were stories that weren’t just about youth dance education and youth programming, but professional and semi-professional groups and companies that carved out a space in Montana and even committed to state-wide and multi-state tours. I felt compelled to revisit a deeper inquiry about my embedment as a performance artist in Montana: Who carved a path ahead of me?

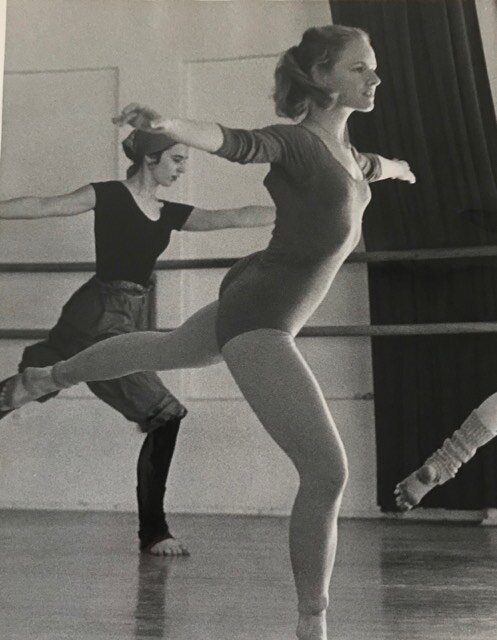

Loos (center) teaching a contact improvisation class at Eastern Montana College (now Montana State University-Billings).

Bess Snyder and Company, Band of Angels by Fredlund. Image L - R: Anne Alexander, Deirdre Alexander, Sirpa Lahiti, Bess Pilcher Lovec, Bess Snyder Fredlund, Amy Aldrich.

“At University of Utah I was studying performance, not teaching, […] when I came back, I wanted to stay involved in dance and in Billings that meant teaching.”

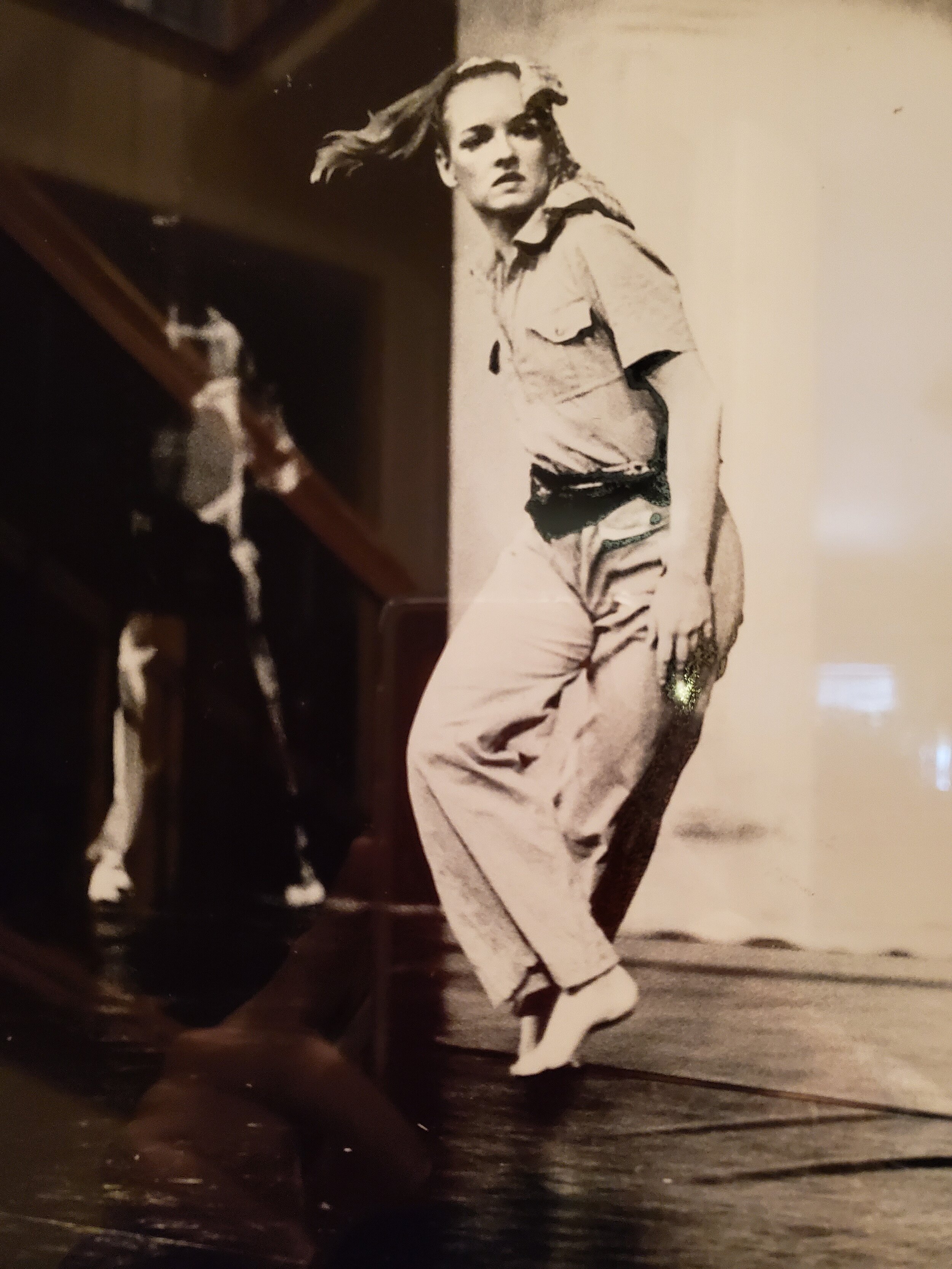

“It was 1974. […] We pitched the idea of a dance company residency to the University of Montana and they bought it. danceMontana became the first professional modern dance company in Montana.”

“I saw an audition notice on a posting board in Utah and flew up to Missoula to audition. […] We were on the road traveling in a van visiting schools and performing in places like Jordan every week.”

As I compiled pieces of stories and individual timelines, I recognized dance makers and educators like Fredlund, Loos, and Lovec were large contributors to the dance performance scene in Montana and also were individuals who had influenced (directly and indirectly) my perception about art making as a young artist. While I listened to their conversation, I noted how their memories included many other influential dance makers, some still creating, and some who have passed on.

I asked them to sit down for a panel discussion to share their memories and experiences based on the suggestion of a creative mentor, “the best thing you can do is talk about each other, tell each other’s stories: record them, share them, document each other’s work.” And while it was not stated, the urgency was evident: make space for fellow artists to tell their stories themselves. I considered how I might apply this practice to inquiries of my own.

“The summer of 1987 I wore out a VHS tape of a recent recital. This was my very first recital with School of Classical Ballet, but I wasn’t interested in my performance. I was entranced with an opening piece choreographed by Fredlund and re-staged on Loos’ students. I was fascinated by dancers breaking the fourth wall, talking on stage, wearing tennis shoes, and moving to contemporary music. I later found out that Fredlund was the first guest artist Loos brought in to set work on her students. This was my first introduction to modern dance.”

“The spring of 1998 I briefly shared the stage with Lovec who brought a comedic character role to a ballet staged by Loos. At a time when much of my personal life wasn’t comedic, I found a lot of resource in physical comedy. I and several other dancers spent the season embracing a silly and precocious performativity that created story and character outside traditional dance forms, something Lovec did effortlessly. This was physical storytelling beyond the starchy ballet pantomime.”

A lot of my research and reflections focus on the transfer of embodied knowledge that is carried into the studio and shared with aspiring dancers. I recognize that those interactions create new intersections, expand connections, and often instills reinterpretation. This transference for many dance artists is an embodied responsibility and a physical dialogue derived from memory. I never worked directly with Lovec or Fredlund, but their brief presence held a resonating influence in my artistic upbringing.

The common question in [Eurocentric] dance introductions is “who’d you train with,” or “what’s your background?” All too often, in my experience, it narrows the scope of influence and memories to a linear line of individuals and dismisses the larger canvas in which those experiences happened.

When I began to document my artistic ancestry and background, I found an entangled web more than a linear path, and much of it is rooted in Montana. My experiences all intertwine. If you were to look at my revised artistic map today, it does not resemble a tree. Instead it moves downward like a subterranean root system with people, places, memories, and experiences entangled together – rather than specific individuals from a single artistic modality. In fact, some of my most influential experiences occurred outside the studio or during opportunities of retrospection.

Reflection offers a lot of vantage and, as an artist working within historiography, memory, and movement ontology, I find it increasingly important to gaze backwards upon the memories that now carry threads of one’s lineage. This requires slowing down … reflecting … sewing individual and collective connections to the past … Which brings me to the gold thread.

“‘I’m sewing a gold thread into you, one that was sewn into me …,’ a teacher told us. She walked to each student, pulling pinched fingers from her sternum and extending her arm to ours, until we all had an imaginary gold thread tethering us together, and to her, and to all who had taught her. I cannot cut that thread. I honor it, and in so doing honor the privilege and responsibility I carry to have an artistic lineage such as this.”

When I first heard those words, I was inspired by this notion of connection via an invisible gold thread and I pressed into the work more. At the time those words instilled a particular work ethic: to be an exemplary artifact of my mentor’s lineage, and I lost myself in the process. I consider my artistic lineage, much of it dance and even more so ballet, to be an embodied bibliography – imprinted on and into me. This gold thread is woven into my movement patterns, wrapped around my joints, and zig zagged through my nervous system. Sometimes it is a sensation of immense mobility and other times restriction. I am entangled in a web of inherited movement language that connects me to individuals of extraordinary influence and remarkable innovation. This was an incredible realization for someone who began their dance journey in a church basement of a small country town with a population of less than 500 people. I often felt disconnected from a culture I was supposed to belong to.

Which brings me back to location – “you are here.” While my dance education has connections around the globe, and through the centuries, my coordinates and geographical embedment as a dance artist in Montana is just as much an influence – in fact I would argue more so. The opportunities that arose from my focused study in dance was, and remains, part of a duality that I reflect upon often in my artistic voice. I find myself wanting to pull on the gold thread and stretch it out so I can have distance from the traditions and structure. I recognize I learned that kind of creative resistance from dance makers like Loos who fostered a balance of learning the craft while not losing a sense of my authentic [quirky] personality in the process.

To pursue a career in the arts in Montana is an undertaking that requires stamina, grit, and ingenuity. This is even prevalent in the performing arts and dance communities because the work is ephemeral and, in comparison to other forms, intangible. I recognize my geographical embedment shapes my relationship to that gold thread and how I am linked to a much more storied history of dance making in Montana. I have witnessed a lot of effort spent looking outward to the trends and artists outside the region and it results in a form of amnesia, regarding the efforts and contributions of those that create[d] and share[d] their art here. This stirred me to start making notes, to be more observant.

A few years ago, I heard about a dance performance that took place in the 1980s. It was staged during a benefit auction in downtown Billings over Valentine’s Day and involved eight dancers in white wedding dresses dragging red tulle fabric around and walking up to people attending the event and whispering, “he must be here somewhere.” It sounded like a hybrid performance art event and delightfully avant garde, even for today. And when I heard it ended with one of the dancers on a table wrapped from head to toe in the red tulle in a ritual fashion it reminded me of feminist artists like Judy Chicago and the Guerilla Girls. This piece was choreographed by Fredlund with Lovec and Loos as two of the eight dancers.

I wondered what other stories I might be missing.

And if I have gained anything from facilitating opportunities to sit down and listen, it’s a healthy dose of perspective. While modern dance might not seem as fresh as the new trends of post-modern and contemporary dance culture today, in Montana during the 1970s wearing pixie short hair, and not wearing a bra while performing would cause pause in a small rural community. Creating artwork for a community of your peers is one thing, but that experience shifts immensely traveling to communities who may have zero awareness of the work you do or the art form you’ve studied. The smallest inspiration can come from a moment of witnessing something new or a realization that art making, dance, can be a profession, even in Montana.

danceMontana on tour to Plentywood Montana circa 1970s. Image: Bess Pilcher Lovec, Cathy Paine, Kata Langworthy and Bob Remley and Ray Spooner

“Did you tell them they’ll also have to wait tables to pay the rent?”

“Well we didn’t tell them everything!”

After the photo shoot, we gathered in around a large coffee table, we shuffled through a collection of photos, concert programs, and newspaper releases from decades past. On the wall hung large pieces of paper with headings on each: “1960s,” “1970s,” “1980s,” “1990s,” “2000s – present.” The conversation trundled along, the stories began intersecting and traveling between the decades, and included a demonstration of Fredlund’s very first solo - a bluebird from the ballet Coppelia.

Initially I intended on taking copious notes, but instead wrote only a few names and dates down. I attuned myself to each of their stories as though I was memorizing a phrase of choreography, or a script. From that visit, my memory weaves and intersects with new thoughts and reflections that I look forward to re-visiting again very soon – but this time with all of you.

Join Loos, Lovec, and Fredlund for a panel discussion Tuesday, January 28th at Art House Cinema 109 North 30th in downtown Billings.

Doors open: 7pm

Panel talk: 7:30pm

Admission is FREE, seating is limited

Reservations available

Apparel “comfortable.” Wedding dresses optional.

More information available at haltforceartcollective.com/press-release

A bit more about the panelists: Fredlund, Loos, and Lovec

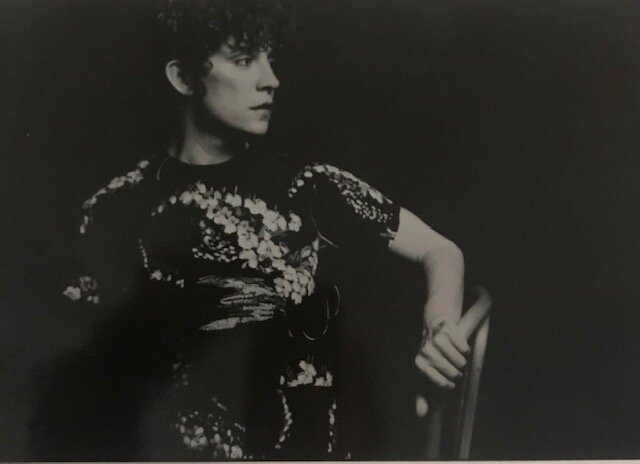

Bess Snyder Fredlund

Bess Snyder Fredlund began her dance career in Billings, Montana, where she studied ballet with Angela McAlpin. She went on to receive her BFA in Theater/Dance from the University of Montana. While in Missoula, she co-founded danceMontana, Montana’s first professional modern dance company. In residence at the University of Montana, the company toured for three years doing teaching residencies and performances in art galleries, schools and theaters throughout Montana and the Pacific Northwest.

Fredlund received her MFA in Dance from California Institute of the Arts and formed her own modern company - Bess Snyder and Company - based in Los Angeles. At the same time, Fredlund became the owner and Artistic Director of THE HOUSE, a studio space in Los Angeles that became the home of her company as well as an active performance space for dance, music, video and performance art. After the birth of her son, Fredlund reached an agreement to turn THE HOUSE over to the UCLA Dance Department and moved with her family back to Montana.

Fredlund has choreographed, performed and taught modern and creative movement throughout Montana through artist residencies with the Montana Arts Council, University of Montana and the Writers’ Voice Project and locally with Ballet of the Prairie, Kite Song School, Rocky Mountain College, CDS The Edge, the School of Classical Ballet and Motion Arts Dance Company (MADCO).

Fredlund received an Artist Fellowship in dance from the Montana Arts Council and was awarded Distinguished Alumni in Dance from Cal Arts.

She was the Education Director of the Alberta Bair Theater for 14 years where she developed numerous award-winning arts educational and community outreach programs. She served five years on the Advisory Committee for the Kennedy Center’s “Partners in Education” program.

A huge advocate of and for the arts, Fredlund produced the first Billings Fringe Festival featuring the work of over 100 performing artists in four different venues on Montana Avenue.

Betty Loos

Betty Loos directed her own school for six years before co-founding the School of Classical Ballet with former business partner Jana Stockton. Betty received her early training from June Austin and Hungarian teachers Ildiko Perjessy and Angela McAlpin in Billings, MT. She continued her training at the University of Utah under the direction of William Christiansen, and at the Teachers' Training Program through the Royal Winnipeg Ballet and National Ballet of Canada. She has furthered her training through numerous intensive workshops with teachers such as David Howard, Fredbjorn Bjornson, and Conrad Ludlow. She was awarded a teacher's fellowship to attend the National Ballet of Canada. Former students have danced with the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, North Carolina Dance Theater, Smuin Ballet, Sacramento Ballet, David Taylor, and apprenticed with the National Ballet of Canada. Betty has also trained in modern dance with Ririe Woodbury, Mark Morris, Bill T. Jones, Doug Varone, and Sandra Neels.

Betty has also served as a Founder, Co-Director and choreographer with the Billings children's community dance company, Motion Arts Dance Company (MADCO) started fall of 2012.

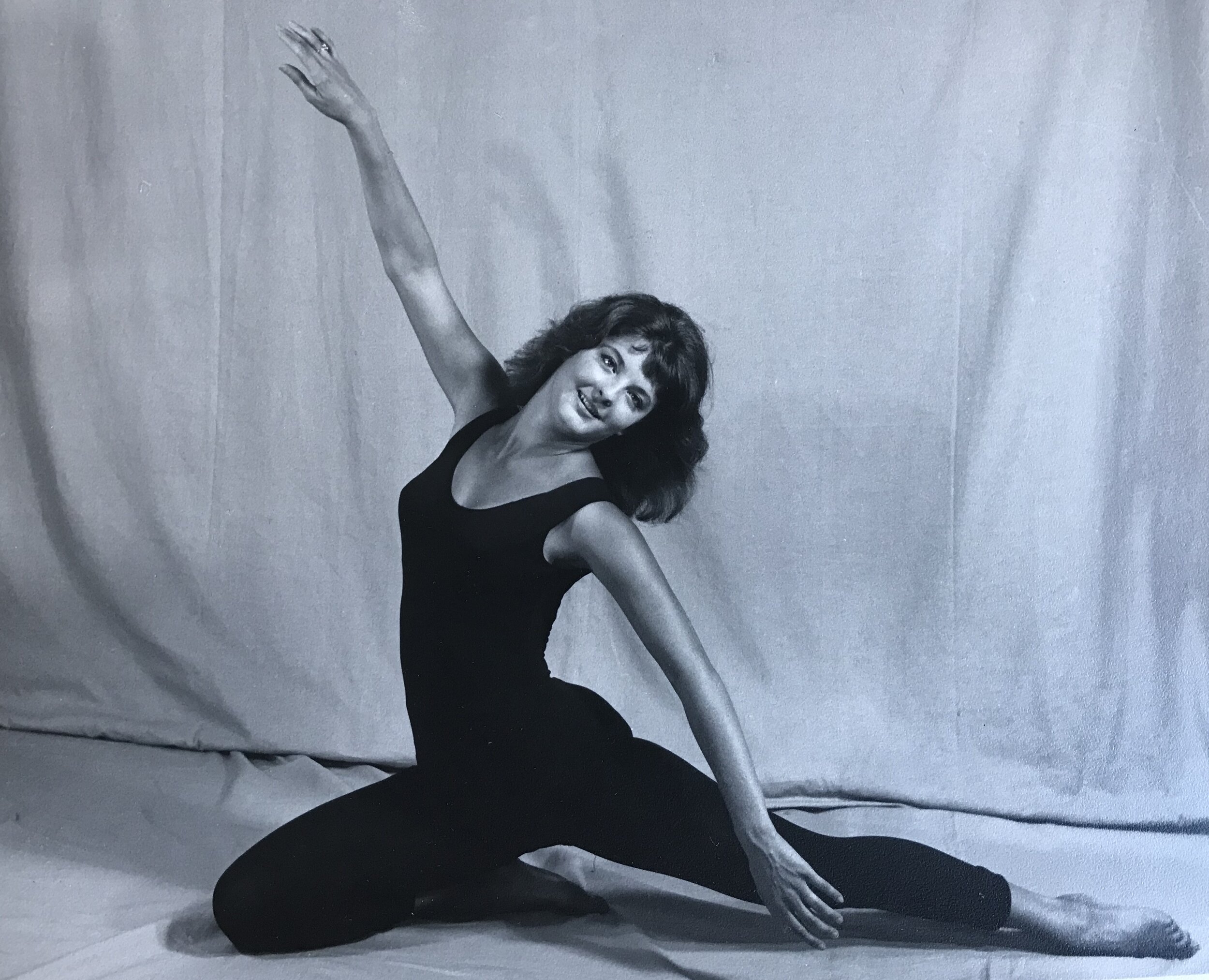

Bess Pilcher Lovec

Bess Pilcher Lovec’s dance education began with Vinnie Fredricks, a former Rockette who studied ballet in New York City with Mikhail Fokine. Lovec later enrolled in the North Carolina School of the Arts as a modern dance major where she worked with, and studied under, Agnes de Mille, Pauline Koner, Gyula Pandi, and Duncan Noble. She also studied technique and performance under former Russe de Monte Carlo dancers: Robert Lindgren and Sonja Tyven. Additional summer training included the Martha Graham School and Alvin Ailey studio, as well as the Herbert Bergof Studio in New York City. Lovec also holds a BFA in Dance, performance emphasis from the University of Utah where she honed her skills for education and choreography.

Among her extensive dance experience, Lovec performed with East Carolina Summer Theater, a professional musical comedy company, however much of her career is rooted in Montana. As a company member of danceMontana, a dance company in residence at University of Montana (Missoula), she performed, choreographed, and taught modern dance for the company, which toured in Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, and Washington. Lovec also taught workshops and performed in Eastern Montana and Northern Wyoming as a member of a semi-professional dance company, Ballet on the Prairie, located in Billings Montana under the direction of Sue West.

Beyond dance, Lovec also holds numerous post-graduate degrees which include a BS in Secondary Education and a MS in Education, Health and Wellness Emphasis both from Eastern Montana College (Montana State University-Billings). She applies her passion for health, wellness, and movement as a hatha yoga Instructor and is a certified NETA Personal Trainer and a certified 500 Hour Yoga Alliance instructor. You can find her holding space at the Billings Community Center, Adult Resource Alliance, and Yellowstone Fitness. She also holds a black belt in Tae Kwon Do and is a Master Gardener.

Lovec spent decades as an educator in the Billings School District teaching English and at Montana State University-Billings working in the Health, Physical Education and Recreation Department where she taught accredited classes in Jazz Dance, Aerobics and Ballroom Dance.

Lovec has served as a consultant, evaluator, and advisor for the Montana Arts Council, and in decades past choreographed for various community productions throughout the years in Billings. She has also given her time to many community organizations as a board member, educator, and volunteer: Yellowstone Art Museum, Rimrock Foundation, Planned Parenthood of Montana, American Association of University Women-Montana, Saint Luke’s Episcopal Church, and Writer’s Voice Awards to name just a few.